The Stearns Pair

Early Nest History

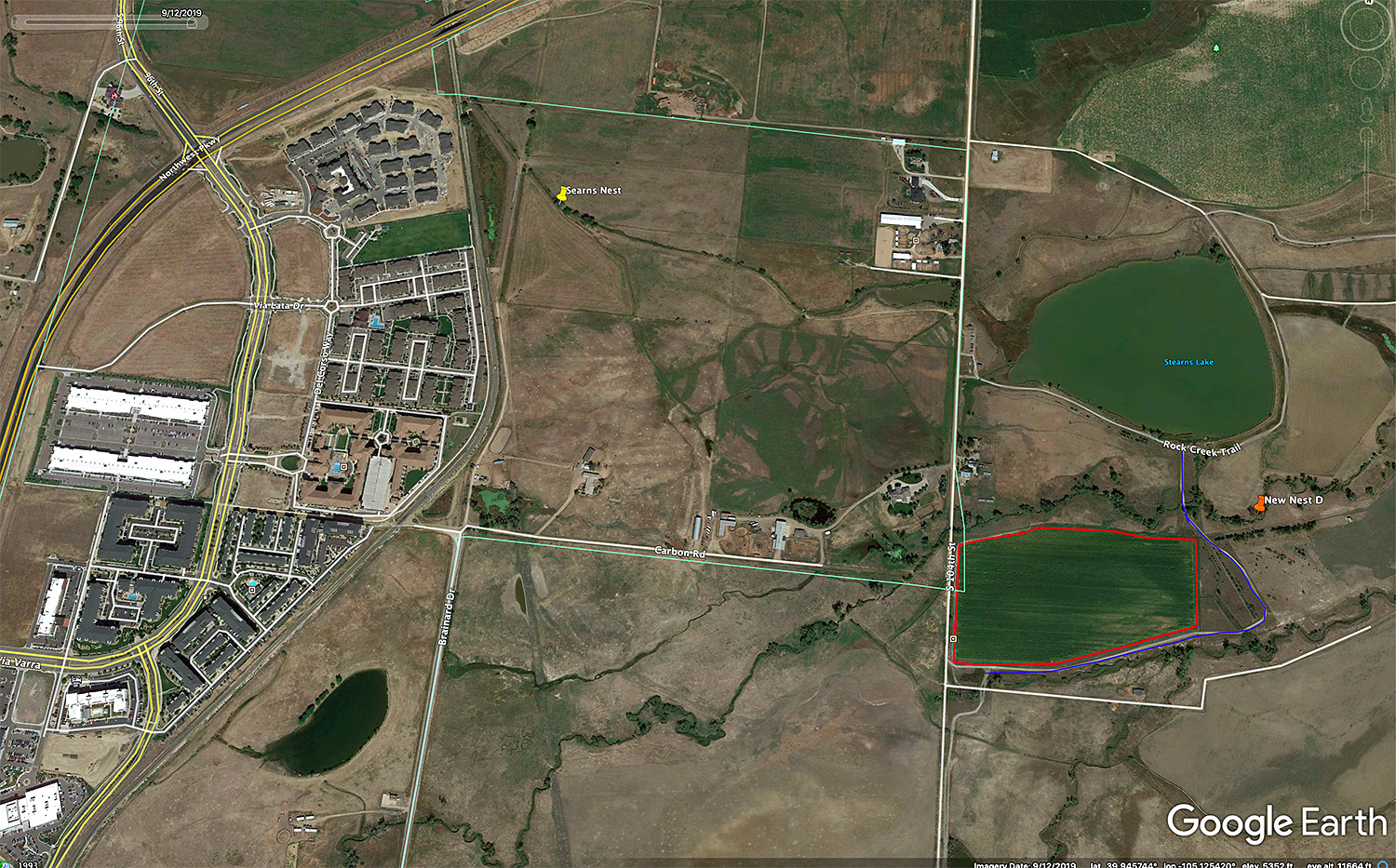

Anecdotal reports indicate that breeding Bald Eagles first occupied the Stearns Lake territory as early as 2010, although first nesting success was not recorded until 2012. They nested successfully during 5 of 7 seasons in their original nest tree from 2012 to 2019. Not only was this nest on private land, but it was also in an enclave of the City and County of Broomfield. Currently, both Boulder and Broomfield Counties remain parties to the conservation easement on that land. Photo 1 is an aerial photograph from June of 2010, which depicts the surrounding landscape during inception of the Stearns nest. At the time, the nearest human development with respect to the nest tree was nearly ¼ mile in all directions, with newly constructed townhomes to the south, and a four-lane parkway to north. Whereas, development has consistently encroached upon the nest area from the west side (photo 2), the Stearns nest territory is surrounded in all remaining directions by nearly 2.4 mi2 (1,540 acres) of largely uninterrupted open land. Much of this land is dedicated open space that is owned by Boulder County.

Photo 1: Aerial photograph from June 2020, showing landscape around the Stearns Bald Eagle nest (yellow push-pin); nearest buildings nearly ¼ mile away.

Photo 2: Stearns nest (yellow push-pin) and landscape in September 2019. Note addition of new townhomes directly west of the nest that were built from 2013 to 2020.

A Treetop Nest (2016 to 2017 Season)

Up until August of 2016, the Stearns nest remained in the northern upper section of the prominent old-growth cottonwood tree (photo 3a and 3b). However, the original nest along with a large supporting limb fell in late August, 2016 (see black circled area; photo 3b). The remains of original nest, along with the broken support branch were strewn in a pile at the base of the nest tree (photo 4). The Stearns eagles wasted no time constructing a new nest, which was well underway at the top of the original nest tree by mid-October (photo 5a and 5b). Poor structural support and extreme exposure to high winds near the mountain front left us uneasy about the nest’s sustainability. Our worst fears came to fruition months later on April 23, 2017, when upon arrival we found the nest partially collapsed and devoid of its recent hatchlings (photo 6).

Photos 3a-3b: a) Stearns family in July 2016, with two juveniles perched at original nest site (northeast quadrant of tree); male below, and female at top of nest tree. b) Original location of Stearns nest in May 2016 with eaglets in nest. Black circle around the supporting branch that fell in August 2016, causing collapse of nest.

Photo 4: Remains of original nest and supporting branch at base of the nest tree. Photo taken October, 2016.

Photos 5a-5b: a) Top nest with male on “ring” perched above female during fall 2016. b) Stearns pair in top nest in December 2016. Male once again on ring perch staring down at female in nest.

Photo 6: Northward collapse of top nest that is conspicuously absent of hatchings; April 23, 2017.

Nest Fidelity and Adult Behavior after Nest-Failure

Both adult eagles were routinely observed over the next 6 weeks following nest failure, which is a testament to the pair’s extreme fidelity to their nest territory (photo 7). Things remained relatively unchanged until June 5th, which was the last time we observed the pair together (photo 8), until later in July. The female disappeared first on June 6th, and the male remained in the nest area for another 5 days (photo 9), after which he too disappeared. During the next month, we cast a wide search for the pair using aerial photos to identify alternate habitat for nesting or a possible summer location—yet our searches always came up empty. The adult male returned to the nest area on approximately July 24th, whereas the female did not reappear until August 4th. The pair’s sudden disappearance was then cause for concern. However, our experience observing this nesting pair over the years has revealed that this short hiatus was an integral and regular aspect of this pairs’ seasonal behavior.

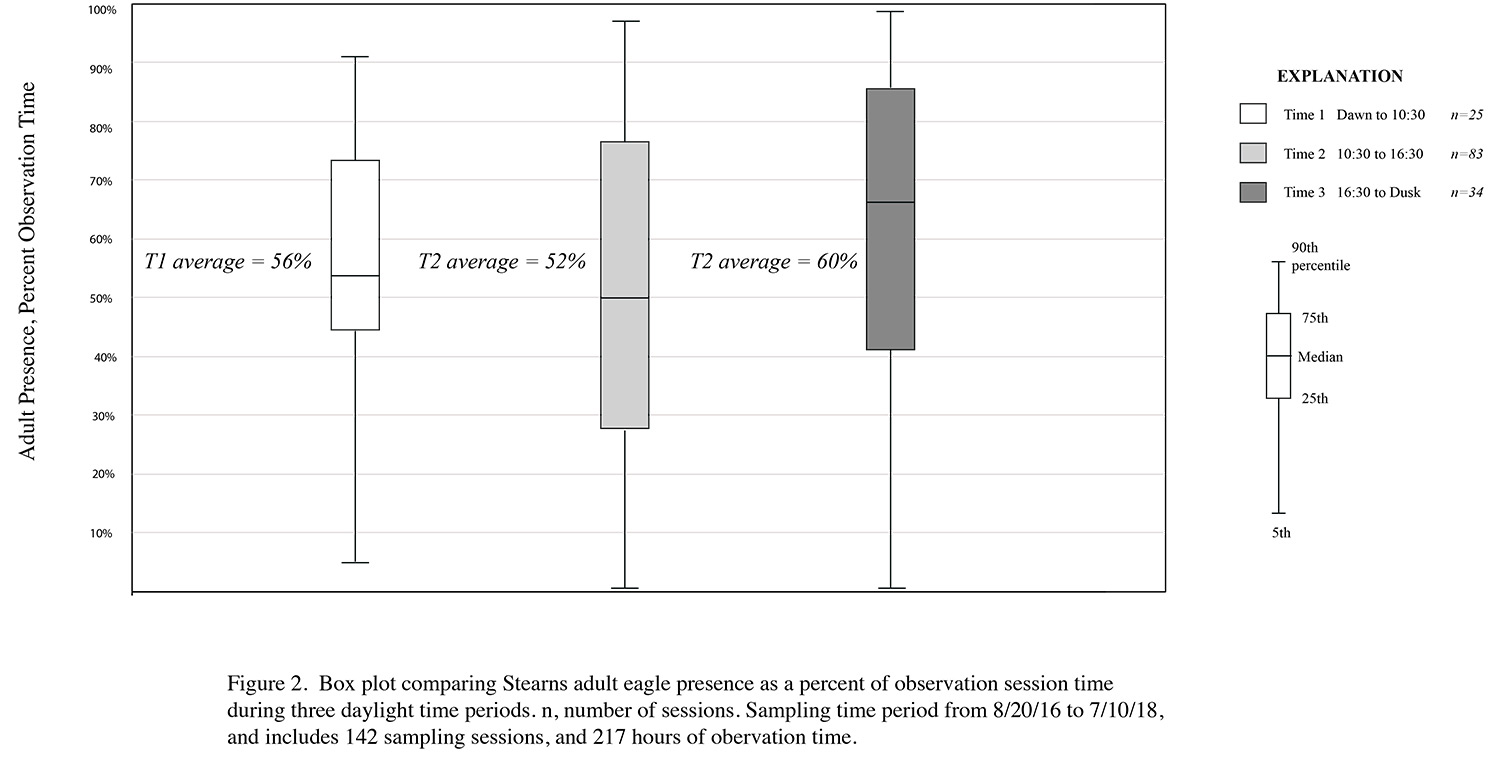

Photo 7: FRNBES data showing presence of Stearns adult eagles (adult presence; percent of observation time) during study sessions in 2016 to 2018. Based on this data, no matter what time of day, one visiting the Stearns near-nest area would have between 52-60 percent chance of seeing at least one of these nesting eagles.

Photo 8: The Stearns pair on a favorite perch just before the female’s (far side) disappearance on June 6, 2017.

Photo 9: Male sleeping in the week prior to his disappearance, 5 days after the female left the area.

Home Construction and Nest “Take” Permit (2017 to 2018 Season)

Early nest building commenced around September 6th, 2017, and to our dismay the pair once again began adding sticks and materials to the collapsed top nest (photo 10a and 10b). To add to the concern, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFW) issued a permit under the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act (BGEPA) in February, 2018, which authorized development of 288 townhomes only 530 feet from the Stearns nest (photo 11). The “incidental take permit” issued by USFW gave the construction company immunity from federal penalty or punishment, which would normally result if the nesting eagles were harmed. FRNBES filed two federal lawsuits to protect these eagles.

An article featured on 9News Website (August 3, 2018) elaborated on the serious problems these eagles faced due to the apartment construction project.

Photos 10a and 10b: a) Male making a grass delivery to the top nest as female awaits. Photo taken about 2 weeks before eggs were laid. b) Adult male bringing in stick to top nest.

Photo 11: Townhome construction project showing Stearns eagles and nest in February 2019.

The Stearns eagles laid eggs in the top nest in middle February, 2018, and hatched three eaglets in late March (photo 12). However, just before the onset of construction, an intense windstorm partially destroyed the precarious nest in mid-April, killing two of the eaglets (photo 13). Once again, the top nest had partially collapsed to the north, leaving barely enough room in the nest corner for the adults to care for the surviving chick (photos 14a-d). Surprisingly, it took nearly three weeks for the eagles to make substantial repairs to the severely damaged nest (photo 15). However, with the adult’s persistence, their young eaglet continued to flourish, and a more stable nest took shape (photo 16). We were pleased to witness the juvenile in pre-flight stages in early June (photo 17a and b), with fledge occurring on June 14th, 2018 (photo 18).

Photo 12: Female feeding hatchlings in precarious top nest (April 1, 2018).

Photo 13: Parents looking over collapsed nest one day after severe windstorm. The surviving eaglet is hidden behind sticks between both adults (April 18, 2018).

Photos 14a-d: Top row a) Female feeding surviving eaglet, both tucked into corner of the nest. Male on ring perch looking over (April 18, 2018). b) Female on ring perch, looking over surviving eaglet that remains in the corner of the nest (April 21, 2018). Bottom row c) Mom affectionately caring for her baby, both barely fitting into the corner of the nest (April 23, 2018). d) Female observing little wings and eaglet on a precarious perch (April 23, 2018).

Photo 15: Female bringing in soft nest material to the badly damaged nest.

Photo 16: Surviving eaglet now sporting juvenile feathers one month after the fatal windstorm. Female is perched on ring above the extensively repaired nest (May 18, 2018).

Photos 17a-b: a)Eaglet and unexpected pre-flight lift aided by oncoming winds. b) Female looking on as her juvenile prepares for first flight that would follow in about 10 days (June 4, 2018).

Photo 18: Typical mobbing of Stearns juvenile by Red-winged blackbirds in the first weeks of flight.

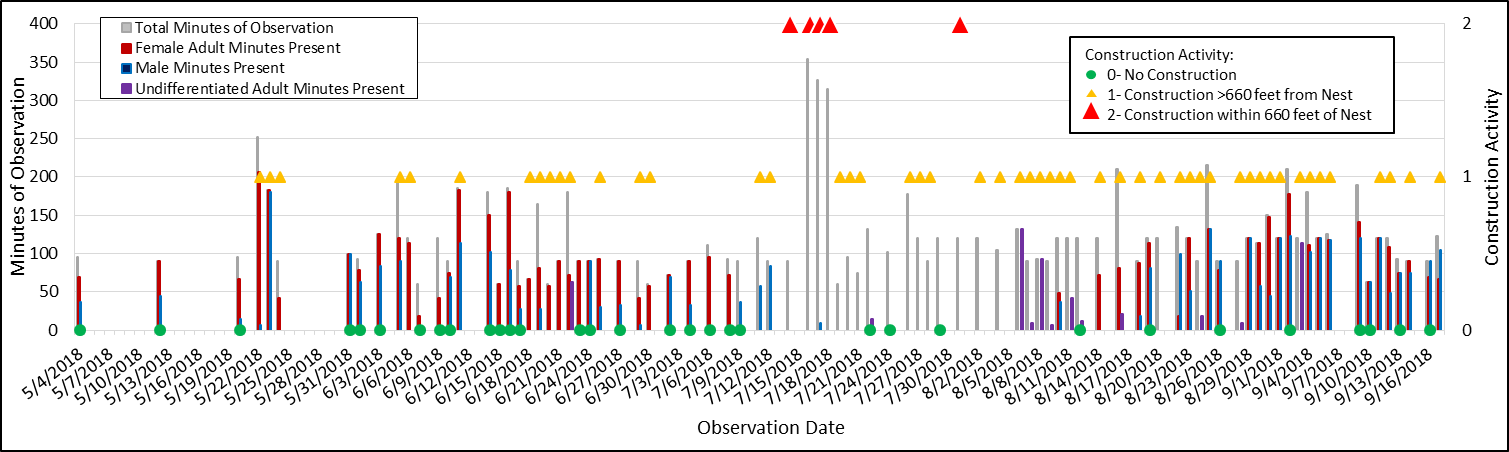

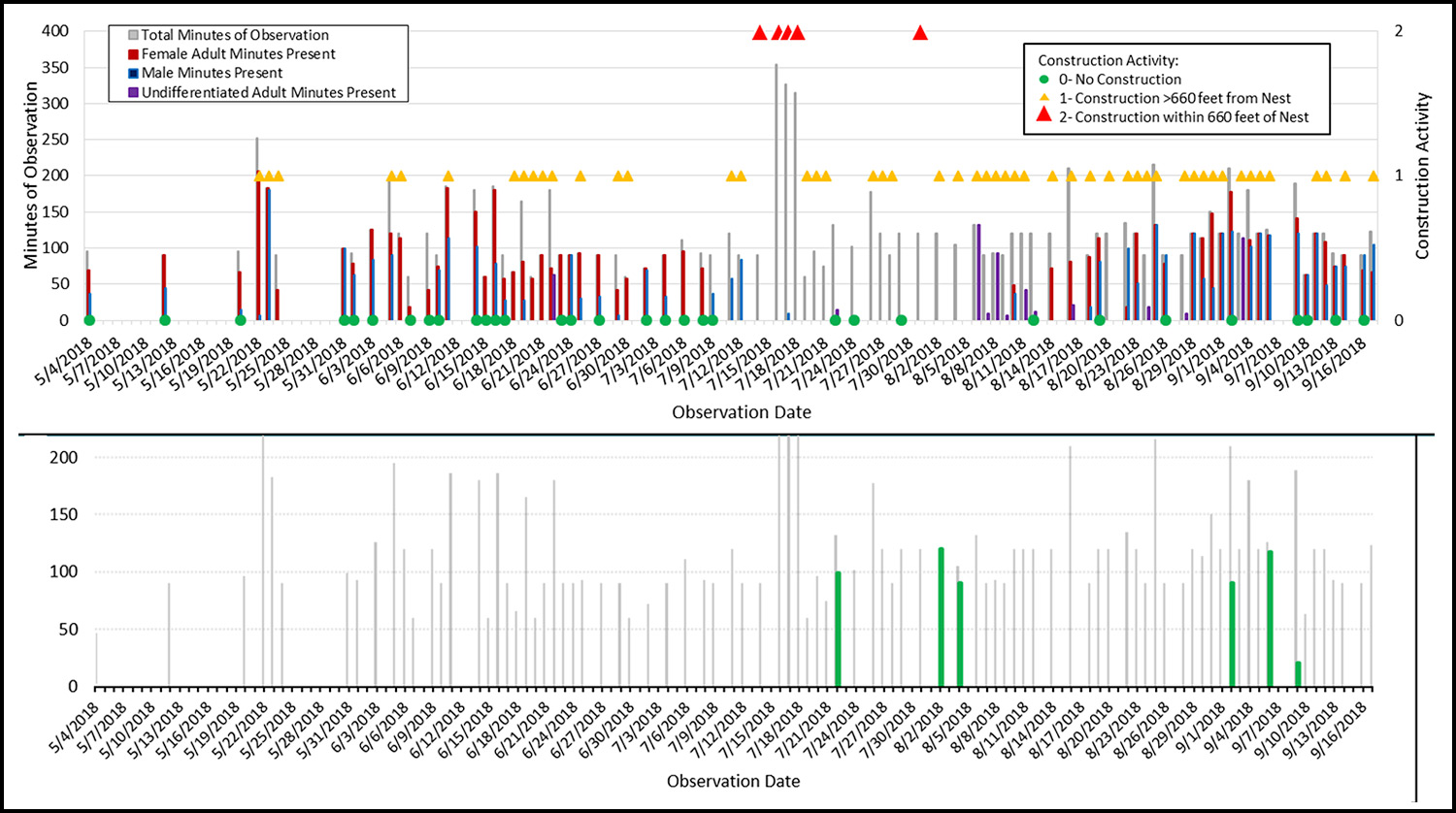

The Stearns eagles with a few exceptions tolerated construction activity from late April through June, as work activity was largely distal to the nest (> 660 ft). This changed abruptly on July 13, as a flurry of loud and heavy construction work began in the area as close as 530 feet from the nest (photo 19). Over the subsequent three weeks (July 14 to August 5), FRNBES data depicts a dramatic decrease in the presence of the adult eagles, dropping from an average of >50% to less than 1% of our observation hours (photo 20).

Photo 19: Beginning of loud construction work less than 660 feet from the nest (July 16, 2018).

Photo 20: Graph of FRNBES data showing adult presence (minutes of observation time) through a nearly 4-month time period spanning early construction activity. Male and female presence denoted in blue and red bars. Red triangles at top of graph represent time period when construction activity was allowed less than 660 feet from the nest. Note that the adult eagles were largely absent during this 3-week time period.

The adult male would briefly appear during these three weeks to provision the juvenile eagle (photo 21). However, the adults’ diminished presence during the critical post-fledge dependence period (PFD) was highly unusual in comparison to FRNBES and other published PFD studies. The juvenile eagle disappeared from the area on July 27th –almost 6 weeks post-fledge–and was observed only once more, nearly two weeks later. The adult male reappeared on August 6th, whereas the adult female returned nearly 10 days later. The decrease in territorial occupancy by the Stearns adults coincided with the arrival of a sub-adult bald eagle. This intruder remained in the nest territory until being driven away in an altercation with the Stearns eagles several weeks later (photo 22).

Photo 21: Adult male during a brief check on fledgling during noisy three-week construction period.

Photo 22. Graph of FRNBES data showing adult presence (minutes of observation time) through a nearly 4-month time period spanning early construction activity. Male and female presence denoted in blue and red bars. Red triangles at top of graph represent time period when construction activity was allowed less than 660 feet from the nest. Note that the intruder bald eagle (green lines on graph) appeared simultaneous to 3-week time period when the Stearns adults were mostly absent.

Behavioral Changes Post Construction (2018 to 2019 Season)

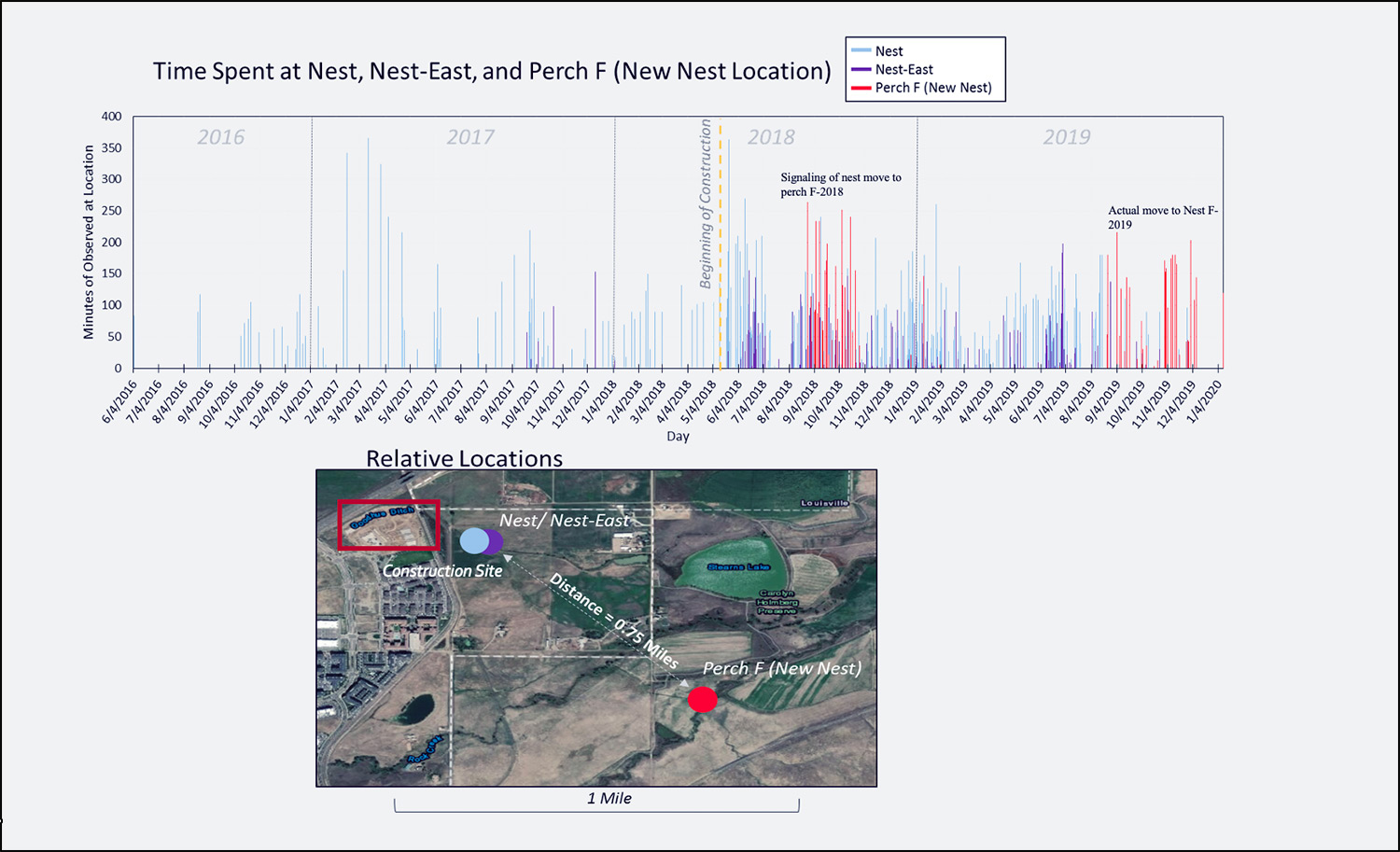

FRNBES time-budget studies document additional behavioral changes by the Stearns adult eagles following the onset of townhome construction. Whereas, the graph in photo 20 illustrates a longer-term disturbance starting in middle July 2018, a variety of more immediate disturbances were also recorded after construction commenced. Cumulative impacts of the housing project can be evaluated by examining the eagles’ behavioral changes following onset of construction. Soon after their 3-week construction-related hiatus, the Stearns eagles suddenly began spending unusual amounts of time—over the next 2 months–in a cottonwood nearly ¾ miles (1 km) from their nest site (photo 23; see Perch F). Behavioral data demonstrate that the eagles were rarely observed in this area distal to the nest prior to construction. Another subtle but important behavioral change occurred after construction: the eagles began favoring the east side of their nest tree, which until fall was largely out of the eagle’s view of construction activity (photo 23; dark blue graph lines denote time at “nest-east”).

Photo 23: Graph of FRNBES data for Stearns adult eagles from during 2016 through 2019. The bars on the graph represent total minutes that the adult eagles were observed during individual study sessions. Presence at the top or west side of the nest tree (in view of construction) are denoted in light blue. Presence on east side of nest tree in dark blue (nest-east; away from construction); time at perch F nearly ¾ miles from the nest tree is in red. Note that time at nest-east and perch F increased markedly after construction began.

Due to the dramatic increase of the eagle’s presence in perch F–during a time coincident with early nest-building activity–FRNBES met with Boulder County Open Space staff to discuss preemptive closure of a nearby trail to allow undisturbed nest-building. Absent the presence of an actual nest, Boulder County staff declined to close the nearby trail.

In late September and to our surprise, the Stearns eagles instead initiated nest building on the east side of their original nest tree (photo 24). Not only was the east side of the tree out of the eagle’s view of construction—at least until the leaves fell—but behavioral data indicates that the Stearns pair began favoring this side of the nest tree after construction (photo 23).

Photo 24. New nest site (see blue circled area; adult eagle with stick) on east side of nest tree (nest-east). Nest construction began before leaves fell and was then out of the eagle’s view of construction.

Construction noise near the Stearns nest diminished after early August 2018, as activity concentrated on foundation work and framing distal to the nest. Yet, from late August through November, the Stearns eagles spent a majority of their time in perches over ¾ mile from their nest tree; something we had not observed prior to construction. Nest building through November was most prevalent through mid-morning, whereas, the remainder of the days were largely spent distal to the nest. Exceptions to this pattern were documented on days when construction activity was either shut down, or markedly subdued. Similar to years prior to construction, we reveled in the eagle’s afternoon presence during these quiet observation sessions (photo 25a to 25d).

Photos 25a to 25d: Adult presence during afternoons markedly increased when construction activity was either shut down or subdued. Top row, L-R: a) eagles on opposite sides of new nest (November 17, 2018; weekend), b) rare sighting of adult male at favorite perch prior to construction (October 13, 2018; weekend). Bottom row, L-R: c) female on top ring perch (September 2, 2018; weekend), d) male on top ring

(October 15, 2018; weekend).

The Stearns pair seemed to tolerate construction activity and reduced noise levels through the fall, and incubation began in mid-February 2019 (photo 26a and 26b). Two chicks hatched about 38 days later near the end of March (photo 27). The appearance of darker juvenile feathers about one month later was welcomed, as the eaglets finally gained protection from the soaking rain and cold of winter (photo 28). Fish deliveries in the month or so post-hatch also notably increased (photo 29).

Photos 26a-26b: a) Female incubating and male perched above. b) female flying in to nest with grasses while male awaits in nest.

Photo 27: Parents staring down inquisitively at hatchlings out of view in the nest; nearing the end of March 2019.

Photo 28: Female feeding eaglets in late April 2019. Dark juvenile feathers are finally coming in.

Photo 29: Male delivering fish to hungry eaglets. Female vocalizes while shielding herself and eaglets as he approaches.

The juvenile siblings began branching in late May, followed by high wing lifts buoyed by steady head winds (photos 30 and 31). Both juveniles recorded their earliest flights on June 10th (photo 32). The precocious nature of the dominant juvenile (JV1) was evidenced immediately upon fledge. Whereas, juvenile bald eagles in their first weeks post-fledge are typically very tentative flyers, JV1 was like a racehorse out of the gate, and its sibling (JV2) was challenged to keep up.

Photos 30 and 31 (L-R): JV1 branching on May 25, 2019, just about 2 weeks prior to fledge. JV1 with a big stationary lift buoyed by oncoming winds as female looks on.

Photo 32: First flights of both siblings; this photo was taken on July 11, 2019.

STEARNS 2019 POST-FLEDGE BLOG (Habituation and Juvenile Eagles)

We were excited to continue our post-fledge dependence studies (PFD), this time focusing on the 2019 Stearns juveniles. It was heartbreaking to lose JV1 only one week after fledge, as she was killed on the highway just ¼ mile from the nest. Her sibling, JV2 kept us busy through the PFD period, and dispersed nearly 7 weeks after fledge. Please take a look at our blog that provides details on this time period; included is an interesting discussion on how habituation of nestling bald eagles to an array of human activity may impact their longevity after they leave the nest.

Mid-PFD Disappearance of Adult Female and Juvenile Dispersal (2019)

The Stearns adult female took an active role in the first three weeks of the 2019 post-fledge dependence (PFD) period, providing food and protection for her fledgling eagles. Yet on July 3, just three weeks after fledge, the Stearns female disappeared from the nest territory. As we observed during two previous seasons, she did not return until nearly one month later (August 6). For the ensuing three weeks, until the juvenile’s dispersal from the nest area, the adult male became the sole parental provider.

Following the female’s departure, the surviving juvenile (JV2) continued to frequent the fields north and east of the nest tree. The adult male commonly delivered prey directly to the juvenile while perched in this area (photo 33), although at times they both shared prey on a prominent horizontal branch on the eastern nest tree. The first documented soaring flight for JV2 was on July 5, a bit more than three weeks after fledge. The observed soaring flight lasted just over 30 minutes, and the playful nature of the young juvenile eagle could be witnessed by paired soaring with two red-tailed hawks—normally anything but friendly in flight with eagles.

The last documented sighting of JV1 was on July 24, thus marking its presumed dispersal at just over 6 weeks post-fledge. The adult male departed the nest territory two days prior to JV2’s dispersal and did not reappear until two weeks later.

Photo 33: Male after making fish delivery to JV2. Photo taken 1 day after female disappeared from area, leaving male as sole provider for the remaining juvenile.

1,000 Cuts—Moving to a New Nest Site (2019 to 2020 Season)

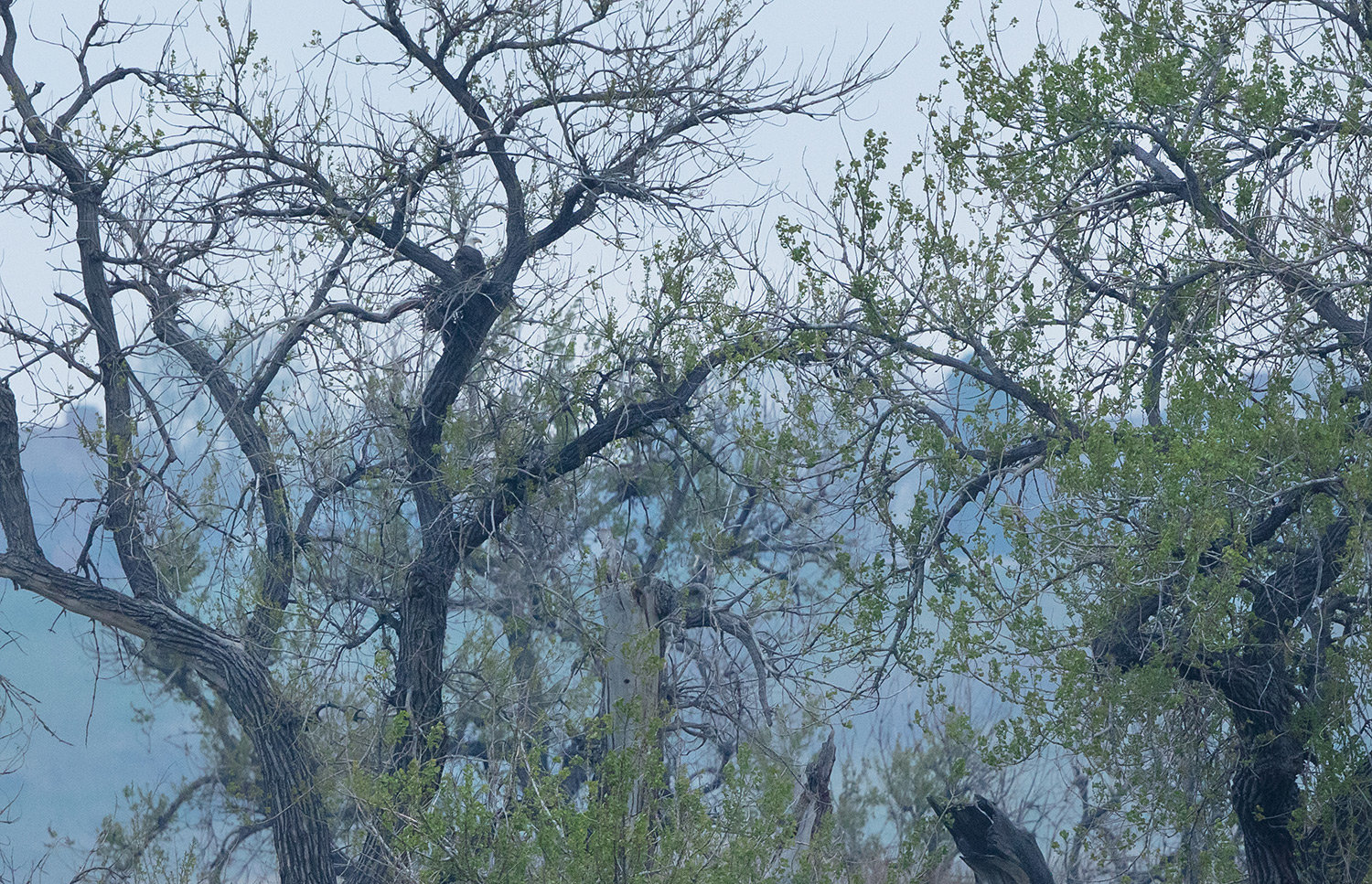

As discussed previously, FRNBES behavioral studies suggest that the Stearns eagles were “considering” a move to another nest site during early fall of 2018 (photo 34). Near the beginning of September 2019, the Stearns eagles once again concentrated their activity in a cottonwood we call perch F, about ¾ miles from their original nest tree (photo 34). Likely due to the ongoing construction activity, the eagles started building a new nest around October 1, in the nearly dead cottonwood named perch F (photo 35). As is typical with nesting Bald Eagles, the Stearns pair chose to re-nest within their familiar nest territory.

Photo 34: Graph of FRNBES data for Stearns adult eagles from 2016 through 2019. The bars on the graph represent total minutes that the adult eagles were observed during individual study sessions. Time at perch F nearly ¾ miles from the nest tree is in red, as noted in both 2018 and 2019. Eagles nested at perch F in 2019.

Photo 35: Early nest-building activity at perch F. Note the poor supporting limb structure for a heavy nest in the upper limbs of this nearly dead cottonwood tree.

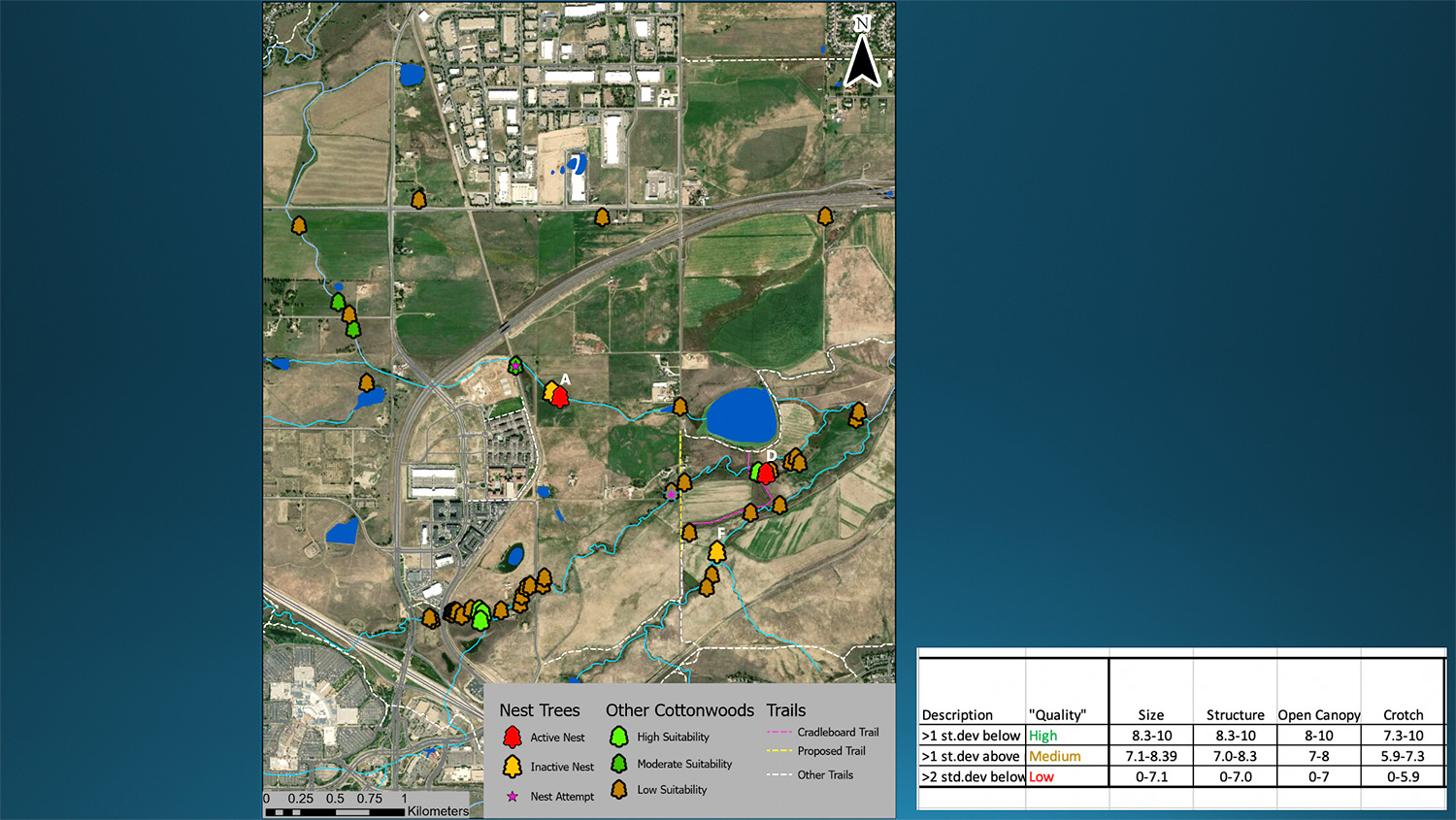

Although a common assumption is that alternate nest trees should be easy for Bald Eagles to acquire, this is arguably not the case across the northern Colorado Front Range. Not only do Front Range Bald Eagles nest only in old growth cottonwoods, but a suitable tree for successful nesting generally requires: 1) a considerable distance from a myriad of potential human disturbances; 2) close proximity to requisite resources; a relatively open canopy; and 3) good crotch structure to support the heavy nests—older nests can exceed 1,000 pounds.

There is a shortage of suitable nest trees in the Stearns eagle’s near-nest area (photo 36; FRNBES unpublished data, 2020). As a result, the eagles likely chose to nest in their best available alternative: a nearly dead old-growth cottonwood with poor supporting limbs for the nest (photo 37). Weekly (or nearly so) photographs documented the westward collapse of the nest, which finally gave way on April 18, 2020, causing the loss of the two nestlings (photos 38 and 39).

Photo 36: Suitability of old growth cottonwood trees in the Stearns nest territory. Tree ranking based on overall size, structure, openness of canopy, and crotch structure. Mapping confined to trees within 2 km radius of original nest tree. The 800 m long “Cutoff trail” is in pink. (FRNBES unpublished data, 2020).

Photo 37: Nearly dead perch F cottonwood prior to nest building. The blue circled area denotes the thin, dead limbs on which the nest was built.

Photo 38: Nest F showing westward collapse of soft upper section in middle January 2020. Photo taken nearly three months prior to final nest failure.

Photo 39: Stearns female with her 2 chicks in nearly collapsed nest, with male looking on. Photo taken on April 11, 2020, one week prior to collapse and death of nestlings.

Boulder County Parks and Open Space (BCPOS) closed the nearly 800-meter long “Cutoff Trail” (see photo 40) in mid-November 2019, because the nest was only about 150 m from the trail. This allowed the eagles to begin utilizing the areas east and west of the “Cutoff Trail following trail closure to derive nest materials, as well as for hunting and perching.

The Cutoff Trail was re-opened after Nest F failed (April 22), and COVID-induced local hiking increased there almost exponentially. The eagles began constructing a new nest soon after at Perch D (see location “D” on photo 36), just 1/3 mile north of Nest F. Most of the nest construction at perch D occurred during inclement weather on May 10-11 when there were few hikers. FRNBES staff and volunteers documented 37.5 hikers/hour in 6 hours of observation from May 12 to 17, 2020. The eagles also attempted to build a nest in Perch A (immediately south of their original nest tree) during April and May, 2020. However, only a few sticks accumulated, likely due to the dense canopy and poor crotch support afforded. Nest building at perch D has been only sporadic and largely confined to the early morning since mid-May. Since Nest D is only 80 m from the Cutoff Trail, it will be necessary to close the trail year-round to give this eagle pair the best chance of success in 2021 and beyond.

Photo 40: Adult female in newly constructed nest at perch D.