The Erie Nest

The Erie nesting Bald Eagles are emblematic of the approximately 200 pairs remaining that live in Colorado, a state that now ranks fifth in human population growth (photo 1). The pace of human development is highest in the northern Front Range (photo 2), home to the Erie Bald Eagle nest and the rest of our study area. Unfortunately, many of the counties in the northern Front Range—including Weld County, home of the Erie nest—lack land conservation programs, and unchecked development is diminishing wildlife habitat at a blistering pace.

Photo 1: U.S Census data from 2017, which shows Colorado to be the 5th fastest growing state in population.

Photo 2 U.S. Census data showing five of the fastest growing counties in Colorado, all of which surround the FRNBES study area.

Everything about Bald Eagles is large, and that includes the territories that they gather resources from and actively defend. In the ten-nest area that FRNBES studies in the northern Front Range, near-nest territories average 1.5 square miles (roughly 720 football fields). Scientific studies conducted by Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW), our state wildlife experts, recommend ½ mile buffer restrictions around eagle nests for nine months out of the year to avoid disturbance. While many Colorado developers have long abided by CPW’s nest buffers, these rules are currently not legally enforceable. Furthermore, federal wildlife authorities have chosen not to enforce federal statutes that protect eagle nests and communal roosts from disturbance, even when violations are scientifically documented.

So what makes the Erie nesting Bald Eagles the “canaries” in the proverbial Colorado Bald Eagle coal mine? The answer lies in their recent history, which documents ongoing struggles with human encroachment over the past four years. These disturbances began with the legal removal of their original nest tree in 2015, paving the way for the construction of 2,200 homes on an undeveloped square-mile tract. Since that time, the eagles have twice moved their nest location, largely due to the difficulty of finding a suitable nest tree and sustainable environment, and their productivity suffered as a result.

Recent History of the Erie Nesting Bald Eagles

Permitted Destruction of the Erie Nest

On December 15, 2015, a wildlife photographer contacted FRNBES and inquired about an old growth cottonwood near Erie, Colorado that had previously housed a Bald Eagle nest (photo 3). He informed us that the big cottonwood was lying on the ground along with several neighboring trees (photo 4). After a number of phone conversations with state and federal regulatory agencies, we were surprised to learn that eagle nests could be legally removed or “taken” via the permitting system of the US Fish and Wildlife Service. The Erie nest “take” was permitted in order to build 2,200 homes on this undeveloped tract.

Photo 3: The Erie Bald Eagle nest in 2013. Photo by Bryce Bradford.

Photo 4: The scene taken about 1 week after the Erie nest tree and adjacent cottonwoods were destroyed according to legal permitting.

Several days after the initial call about the Erie nest “take”, we visited the site on a cold and snowy day. We spotted the nesting Bald Eagle pair perched on an oil pumper, just behind the hulk of their former nest tree, which was lying in a tangle on its side (photo 5). Determined to document the fate of these two pair-bonded Bald Eagles after their nest has been removed, we continued to visit the old nest over the following weeks.

Photo 5: Erie Bald Eagle pair on oil and gas pumper behind the toppled remains of their nest tree.

Following the Erie Pair to a New Nest Location (Season 1)

During that time frame, we spotted the pair flying northwest and followed them to a site about 2 miles from their former nest. We were delighted to find both Bald Eagles the next day near where they disappeared the previous evening. The female was perched near the top of a weathered old growth cottonwood (photo 6), while the male was in an adjacent cottonwood. A new nest began to take shape in that old cottonwood during the next month (photo 7). There are many possibilities why the eggs laid in that nest failed to hatch after 55 days of faithful incubation (35 to 38 days is the average). First, this was a new pair, as the former male had been electrocuted near the old nest site only a month prior to the nest “take”. Other factors could have been the stress of setting up shop at a new nest; inexperience of the new, young male eagle (3.5 to 4 years old); or perhaps due to temporary egg abandonment on a frigid March day as a ditch excavator operated near the base of their nest. More of the Erie Bald Eagles in this new nest year can be seen in this short slide show with original music.

Photo 6: Erie adult female perched upon the site of their future nest in early January 2016.

Photo 7: Erie female launching from the new nest tree.

Season 2 at the “New” Erie Nest

Like all nesting Bald Eagles in the Colorado Front Range, the Erie pair continued to maintain their nest site through the following season, and began incubating eggs in late February 2017. A sense of this often-peaceful setting during early incubation is captured in a slide presentation, once again with original music.

After well over a year since the tragic loss of their former nest, and the previous year’s nest failure, it was heartwarming to witness two hatchlings appear in late April (photos 8 and 9). The female Bald Eagle demonstrated a ferocious determination to protect and cover her babies through the many soaking rain and snowstorms during April and May (photo 10). On the morning of May 23, we received an early call from a farmer friend that lives adjacent to the nest—the nest had fallen during the night (photo 11). The old cottonwood supporting the nest could withstand no more of the incessant moisture, and both 7 week old eaglets fell to their death, along with the nest that evening.

Photo 8: Erie male tending to his two eaglets during the second season in the nearly dead, old-growth cottonwood.

Photo 9 Erie female taking flight leaving her two eaglets during the second season nesting in the nearly dead cottonwood tree.

Photo 10: One of the many May 2017 snowstorms and the Erie female covering her two almost full-grown eaglets.

Photo 11: Remains of the nest that fell on May 22, 2017 after numerous wet snowstorms.

The Erie Pair Find Yet Another Nest Location (Fall of 2017)

Once more, the Erie Bald Eagles faced the challenge of finding a suitable nest tree replacement. Not only are old-growth cottonwoods the only nest substrate used by Bald Eagles in the Colorado Front Range (photo 12), but our studies indicate that these massive trees need to meet several additional requirements: 1) significant distance from human activity (typically ¼ mile); 2) relatively open canopy for entry, exit, and field of view; 3) proper branch structure on which to build a nest; and 4) proximity to waterways and other food sources. Another limiting criterion is that when nesting Bald Eagles are uprooted or choose to relocate, they prefer to re-settle nearby. Our studies of ten Bald Eagle nest relocations in the northern Front Range indicate that the average nest move is only 0.6 miles (1km).

Photo 12: Three old-growth cottonwood nest trees in the FRNBES study area.

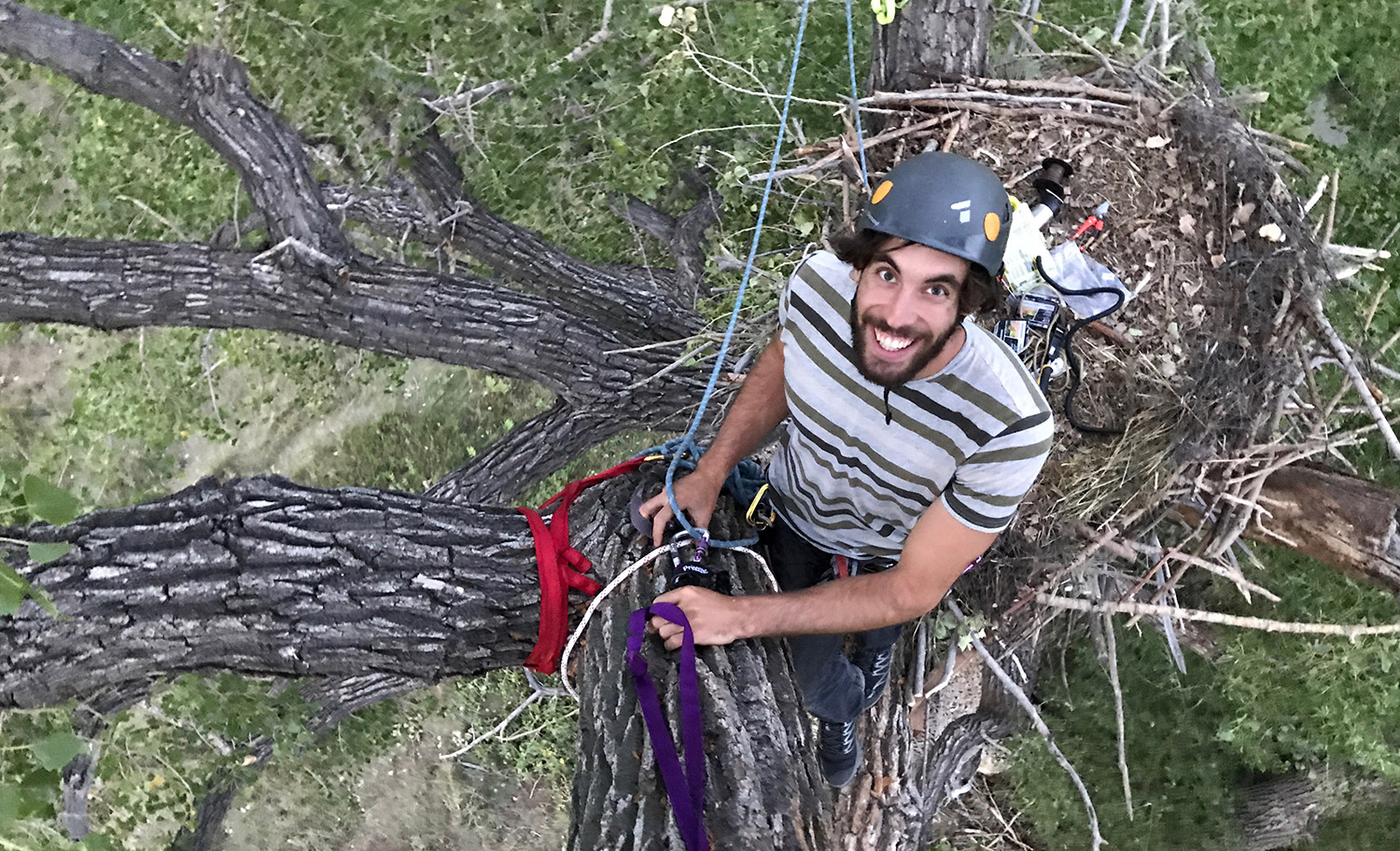

During a careful survey of old-growth cottonwoods within one mile of the recently fallen nest tree, we were unable to identify any trees that met all of the above-stated requirements. A decision was made—a team from FRNBES would build a new nest on a platform, just a couple of trees away from their old nest tree (photo 13 and 14). Although we built an awfully nice nest, the Erie eagles passed on this location. Perhaps it was the frequent haying on the adjacent farm, or really who knows what else. Instead, they began building a new nest in September, 2017, about ¾ miles to the south within their original near-nest territory. We didn’t spot this new nest until mid-October, and were thrilled to discover both eagles up in their home.

Photo 13: Nearly completed nest constructed by the FRNBES team.

Photo 14: Finishing touches on the platform nest.

So how did we miss this old-growth cottonwood in our survey? The likely answer is that the Erie eagles were forced to compromise, this time choosing a well-suited tree, in their familiar territory, near abundant prey, but out of necessity closer to human activity. Their new home is situated on a quiet agricultural horse property, with a dirt access driveway passing only a few meters from the base of the tree (photos 15a to 15c). This tree likely served as a perch prior to being selected as a nest tree, allowing the eagles to become accustomed to the low-key human activity over time. When left without other good nest site options, they settled for a location that they knew well.

Vertical Photo 15a: Resident of horse ranch walking up the two- track driveway that passes near the Erie Bald Eagle nest. Male adult is perched above nest and vocalizing as the walker approaches. Top photo on right (15b) – Resident walking along dirt drive near Erie nest tree. Bottom photo on right (15c) – Zoom of Erie male eagle (from photo 15a) vocalizing his displeasure as walker approaches.

From the history of the Erie nest and of several others, it can be argued that Bald Eagles are being forced into more marginal nesting situations in eastern Boulder and western Weld Counties, likely contributing to these nest failures—especially if eagles are compelled to nest in unsafe trees so they can distance themselves from oil wells, subdivisions, and other disturbances.

2018-Finally A Successful Season for the Erie Nesting Eagles

Following four consecutive failed seasons, the Erie nesting Bald Eagles finally fledged three juveniles in June, 2018 (photo 16). Likely one of the more important factors in the 2018 season’s success is the stability of the nest, which is buttressed in a well-supported and stable crotch in the upper reaches of a relatively healthy old-growth cottonwood (photo 17). In early April of 2018, intense windstorms with gusts up to 89 mph swept the FRNBES study area, destroying four Bald Eagle nests, yet the Erie nest survived. The Erie eaglets were well-protected, both by the vigilance of their parents and the stability and positioning of the nest.

Photo 16: Erie female and three eaglets in May 2018.

Photo 17: Erie nest tree and Erie Bald Eagle pair. The nest is held in a strong supporting crotch in the upper reaches of the old-growth cottonwood.

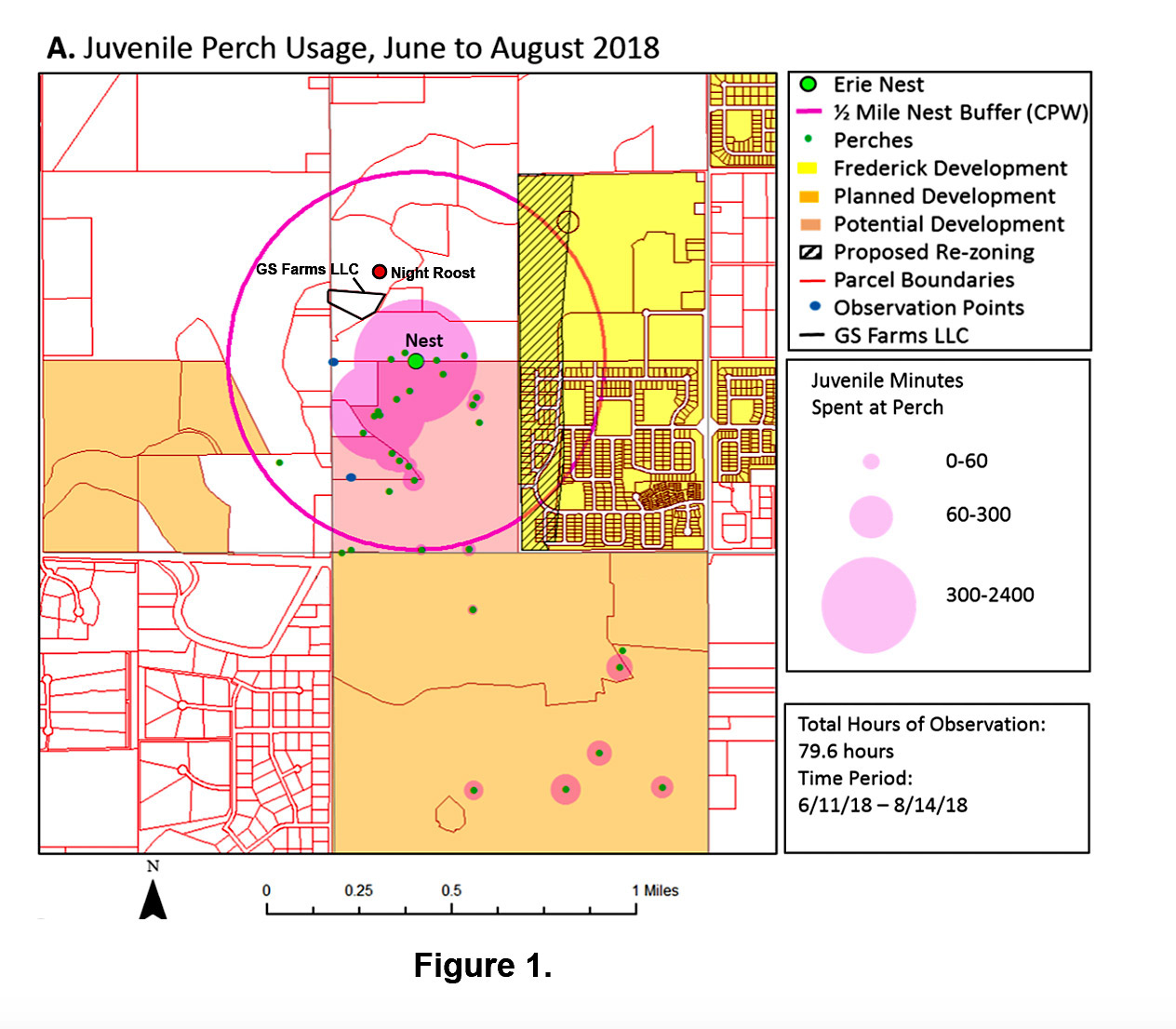

Comprehensive studies by FRNBES (photo 18) documented how these three juvenile eagles used the surrounding terrain during the 2018 post-fledge dependence period (June 11 to August 14), a time during which the juveniles can fly yet remain within their nest territory. As we have found during our other post-fledge dependence studies, the three Erie juveniles relied upon their parents for food and protection.

Photo 18: FRNBES map showing use area of the three juvenile Bald Eagles during post-fledge dependence in the summer of 2018. Note the CPW ½ mile recommended buffer in pink; perches (green) and differing size solid pink circles denoting relative time at perches; planned development in yellow and orange; and potential development in salmon.

As shown in photo 18, the 2018 fledglings utilized an area that extends well outside Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s recommended ½ mile buffer, within which all human activity is to be restricted nine months out of the year to avoid unlawful disturbance of eagles. It is certainly discouraging to learn from land use documents that the entire eagle use area and much of the adjacent land is either already planned for near-term development, or will likely be developed in the future.