Stearns 2019 Post-Fledge

August 19, 2020

2019 Post Fledge Dependence (Herding Cats)

In the initial two weeks post-fledge, the adult and juvenile eagles focused most of their activity in an ~130-acre area of the hay fields north and northeast of their nest (photo 1). The adults were busy tending to the two active juveniles in what we call the early “herding cats” phase of the post-fledge dependence period (PFD) (photo 2).

Photo 1: Parent keeps close watch over JV2 in fields north of the nest tree.

Photo 2: Adult eagles flank JV2 just a few days after fledge; eagles are perched on fence surrounding cattle operation on open space land northeast of nest.

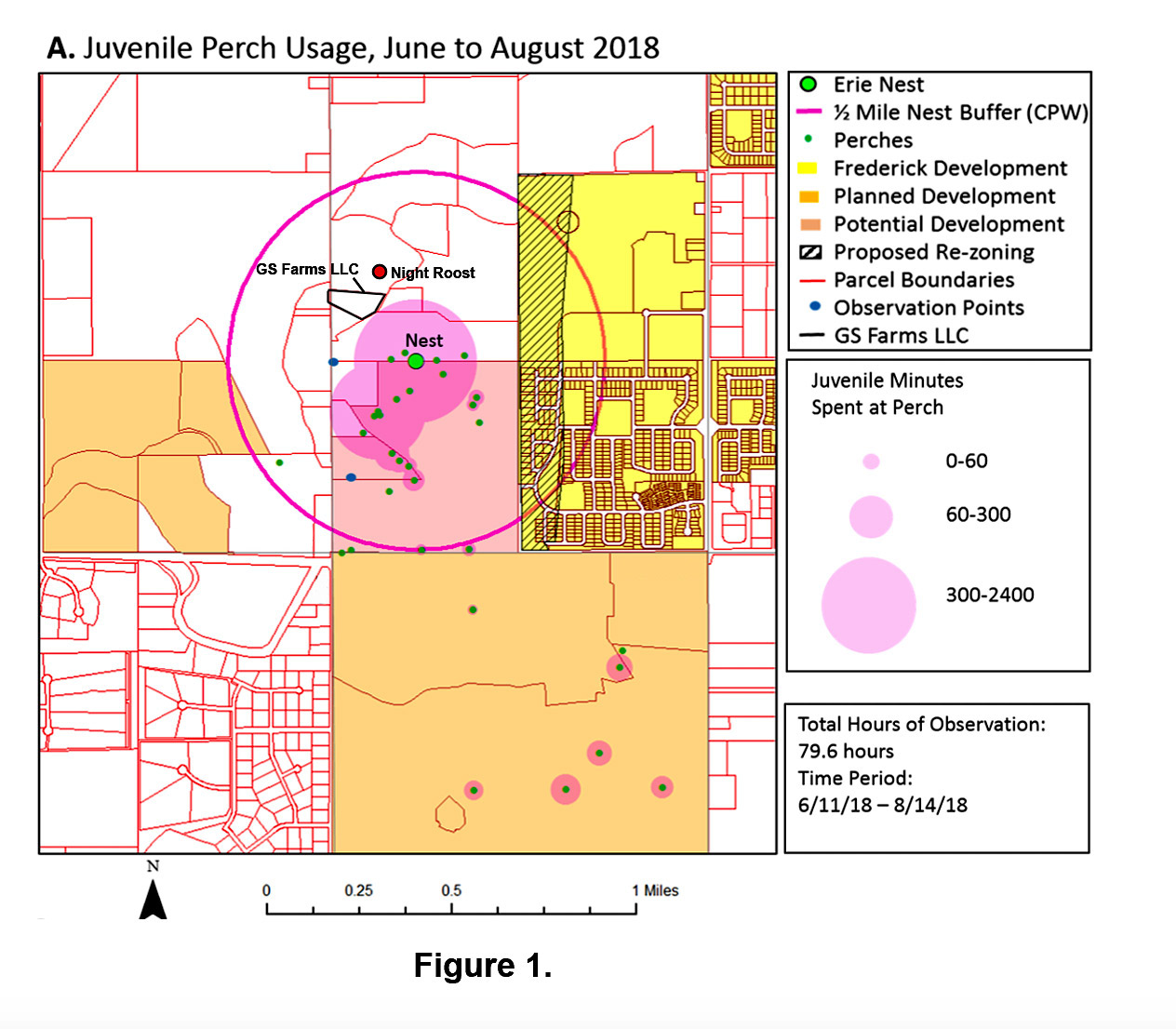

The colored circles in photo 3 represent proportional time that each of the four eagles spent at individual perch localities (black dots) during these two weeks following fledge. Increased time at each perch location is represented by relatively larger ring diameters. With exception of the nest tree, perches were typically on the ground or atop fence posts. During this time, the parents often remained in close proximity to the juveniles, supplying them with prey, or on a couple of occasions, diving upon coyotes that approached the unwary juveniles. Ninety acres of this area is protected open space owned by Boulder County, and the remainder is private property under a joint conservation easement. These protections end abruptly about 1/4 mile north of the nest with a 4-lane highway, and 600 feet to the west with a railroad track, townhomes, and an assortment of new developments.

Photo 3: FRNBES data showing relative time at perches for of all 4 Stearns eagles in the two weeks after fledge. Larger rings represent increasing time at perch locations (black dot). CPW recommended 1/2 mile nest buffer gives scale of post-fledge use area. Note highway in orange at about ¼ mile north of nest tree (yellow star).

Loss of JV1

Just six days post-fledge, we became concerned when JV1 began lingering near the almost-completed townhomes, and less than 200 feet from the adjacent highway (photo 4). The following day (June 17), we observed JV1 once again less than 200 feet from the highway, this time attended by the adult female, who had just delivered a prairie dog to the young eagle (photo 5). This was the last time we observed JV1, as she was reportedly killed on the highway during the next day or two. The sudden and nearly week-long absence of JV1 so early in the 6 to 8-week PFD period, did not bode well, as the sad news of her fate later confirmed.

Photo 4: JV1 on solar panel near new apartment complex and highway.

Photo 5: Stearns female just after bringing prairie dog to JV1 (circled in blue). Location is less than 200 feet from 4-lane highway.

After the loss of JV1, the remaining juvenile continued to frequent the open fields north and east of the nest. On several occasions, both adult eagles would take up flanking positions between JV2 and the highway, not more than 500 feet to the north (photo 6). Since this positioning was observed repeatedly during this time frame, it prompted our curiosity as to whether this could be an intentional protective behavior by the parents. In the same time period, we also observed the adult male land with a prairie dog next to JV2 when perched < 350 feet from the highway (photo 7). Rather than leaving the prairie dog for the juvenile, the adult male flew with the prey back to the nest and was immediately followed by JV2 (photos 8a and 8b). Whether this was an intentional ploy or not, we were glad to see the young eagle drawn away from the busy highway.

Photo 6: Both parents taking up flanking positions between the JV2 and 4-lane highway. Photo about 1 week after JV1 was killed on highway.

Photo 7: Male with prairie dog perched just below JV2; both about 500 feet from 4-lane highway.

Photos 8a and 8b: a) Male flies back to nest with prairie dog, and b) male and JV2 on feeding branch immediately afterward.

Habituation to Human Activity—Is it Always a Good Thing?

The 2019 Stearns eaglets spent 62 days raised in a nest less than 600 feet from a busy townhome construction project (photo 9). While a major concern with construction activity so close to a nest is potential nest abandonment, little consideration is given to potential impacts on the juvenile eagles being raised in the nest—particularly long-term. It is well known through numerous scientific studies that animal habituation to human presence results in desensitization to disturbance over time. Furthermore, a common assumption about habituation can be summarized in a recent email communication from a local volunteer raptor specialist and conservationist: “[the Stearns eagles] have demonstrated amazing resilience in recent years as have other Bald Eagles in the area. Habituation for this once imperiled species can only be a good thing.“ Considering FRNBES experiences with post-fledge juveniles and a few key scientific studies discussed below, we question this blanket assertion.

Photo 9: Stearns nest and adult eagles in context of large townhome project only about 660 feet away.

Millsap and others (2002), conducted a study that compared the survival of 35 “rural” versus 35 “suburban” fledging Bald Eagles during their first year. For more information, see Comparative fecundity and survival of bald eagles fledged from suburban and rural natal areas in Florida. At the end of the first year, survival of rural fledglings was 89% compared to 65% to 72% for suburban fledglings. Six of 7 suburban eagles for which reason for death could be determined was human-caused, primarily from electrocution or vehicle collisions. None of the four rural Bald Eagles for which cause of death could be determined was from anthropogenic causes (human-related). The authors of the study hypothesized that the suburban Bald Eagle fledglings were more acclimated to dangerous anthropogenic features than were rural eagles, and once independent did not regard them with the same degree of caution.

Our behavioral observations of fledgling Bald Eagles are certainly consistent with findings by Millsap and others (2002), who further suggested that habituated juveniles may be more desensitized to potentially dangerous circumstances once out of the nest. A recollection of the Stearns juvenile (JV1) in 2019–only 6 days post-fledge–perched on a solar panel next to newly constructed townhomes and a four-lane highway, comes to mind (photo 10). This juvenile was killed on the same highway only a day or two after the photo was taken. Just two weeks later, we watched the remaining sibling (JV2), after being caught aloft in gusty winds, blown in and out of oncoming traffic on the same highway. This horrific scene, with multiple near collisions, played out for more than five minutes, until the juvenile disappeared from view. After fearing the worst, we returned more than an hour late to find JV2 perched safely in the nest tree. After the recent heartbreak of losing JV1 on the same highway, this was certainly cause for joy.

Photo 10: Close up of JV1 on solar panel next to townhomes just 6 days after fledge.

Perhaps more compelling are examples of fledglings from the Erie nest, where a two-track rural driveway passes nearly 20 feet from the nest tree. In 2018 and 2020, during the first two weeks post-fledge, we witnessed juvenile eagles remaining “unflappable” in the driveway, seemingly unfazed by the homeowners in vehicles waiting to pass (photo 11). Yet, more disconcerting was finding the Erie fledglings in 2018–only two weeks post-fledge–perched on high hazard power poles along a busy two-lane highway (photo 12). While FRNBES collaborated with a local power company to mitigate the electrocution risks (see Partner with us section), the collision hazard on the highway below remained.

Photo 11: Juvenile in driveway near the Erie nest in 2018, seemingly oblivious to approaching tractor.

Photo 12: One of three juveniles from the Erie nest in 2018 perched on a high hazard utility pole within ½ mile of the nest.

Whereas the lone Erie fledgling in 2020 twice refused to yield quickly to vehicles along the driveway near the nest, we witnessed strikingly different responses from its juvenile half-sibling from the nearby CR16 nest. Situated along rural Boulder Creek, the CR16 nest is more than ¼ mile from the nearest rural dwelling and adjacent dirt road. In the weeks post-fledge, we attempted to observe the CR16 juvenile three times while it foraged on the banks of a pond.

During each of the three attempts, we approached slowly and remained in our vehicle. Even though we parked on the opposite side of the pond at 0.2 miles distance, the CR16 juvenile flushed each time within seconds of our arrival (photo 13). It is interesting to note that both CR16 adult eagles are also relatively intolerant to human presence in their nest territory. On multiple occasions we have observed the CR16 adults flush from the nest area or common perches when pedestrians or vehicles approach within ¼ mile (photos 14a and 14b). Typical of Bald Eagles when disturbed by humans on foot, we have also observed the CR16 male flush and circle hikers, even when approaching more than ¼ mile away.

Photo 13: CR16 juvenile in 2020 that flushed upon arrival of vehicle at 0.2 miles away. The same scenario was repeated twice more in the following weeks.

Photos 14a and 14b: Photo on left shows CR16 male flushing from close proximity to nest at ¼ mile from hiker; (see arrow pointing to circle). Photo on the right shows the CR16 male atop perch vocalizing upon arrival of vehicle nearly ¼ mile away.

Post-fledge dependence studies by FRNBES indicate that fledgling Bald Eagles spend most of their time perched and exploring an area within 0.3 to 1-mile radius of their nests (photo 15). During this time frame, the young eagles are still fully dependent on the adults for food, occasional protection, and adaptive study of their parents’ behavior. Habit protection is essential during this 6 to 8-week PFD time period, when flight and other basic skills are rudimentary. During this vulnerable time period, all anthropogenic dangers are best minimized—certainly the more protected open space the better.

Photo 15: FRNBES map showing use area of the three juvenile Erie Bald Eagles during post-fledge dependence during summer of 2018. Note the Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) ½ mile recommended eagle nest buffer in pink; perches (green) and differing size solid pink circles denoting relative time at perches; planned development in yellow and orange; and potential development in salmon.